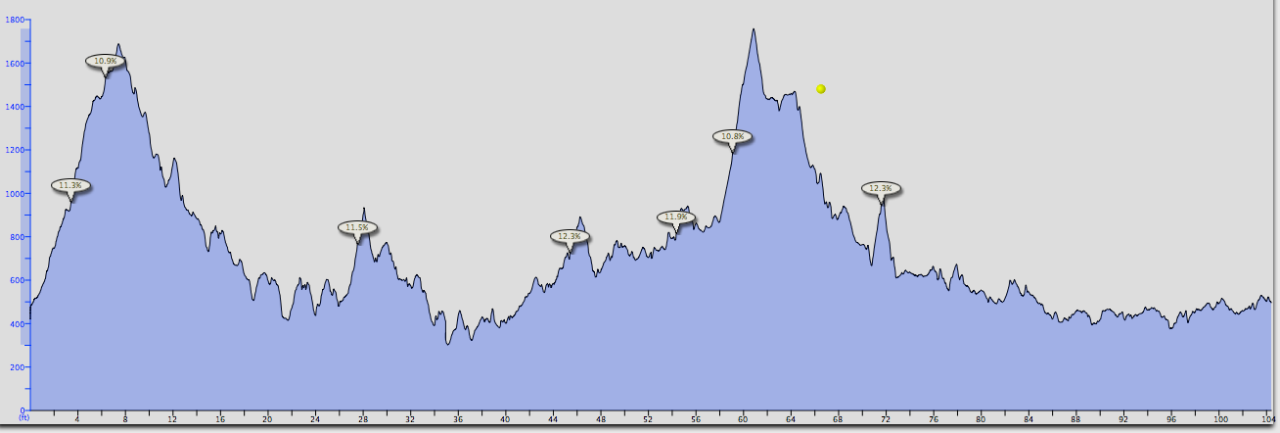

Last Sunday during the Civil War Century, I was eagerly anticipating a certain climb that I remembered from riding the event 2 years ago. The climb was relatively long (10 minutes or more) on an open two-lane road with wide shoulders at a steady gradient of less than 8 percent. I remembered it as a great climb for testing purposes, in that you could pace yourself without regard to changing gradients or other distractions. You could also see up the climb far enough to target riders to pick off as you climbed. Basically, I was planning on hitting the climb as hard as I could to test myself, hoping to get a solid 20-minute effort out of it.

But the course designers played a trick on me – about 5 minutes into the climb, the route turned off the main road and went up a steeper, more narrow climb to the left. I had to slow down for the turn due to oncoming car traffic and then attempt to recalibrate my effort for a steeper climb of unknown duration. Needless to say, my pacing strategy was thrown for a loop. I stayed on the gas, but my power dropped a few times as the road leveled off and then resumed at the same or steeper gradient. Dealing with the steeper gradients wrecked my carefully calibrated effort and took me over the edge, forcing me to back off more than I wanted. Eventually I could see the end of the climb and a host of riders clumped together. Summoning a final burst of energy I picked up the pace and rode past everyone by the summit.

Given the variability of the terrain, the gap between average and normalized power was fairly wide. NP was a solid (but not great) 304 watts for the 20-minute effort. I was hoping for something above 315-320.

The climb is perfect illustration of a concept I’ve been reading about recently: anticipatory regulation. In a nutshell, anticipatory regulation is a model for explaining the onset of fatigue in endurance sports. According to the model, the brain regulates the distribution of effort during exercise by continuously calculating the maximum level of muscle activation that can be sustained until the anticipated end of the task without harming yourself. In an event of known duration, it allows for an “endspurt” of higher effort – that sprint at the end of race or that extra burst of energy at the top of the climb. According to the theory, your mind automatically slows you down before you harm yourself, regardless of whether your muscles could have continued working at the same rate.

Anticipatory regulation is one of two competing theories of fatigue, the other being peripheral fatigue. Peripheral fatigue is a totally involuntary and is the function of biological processes in the working muscles. A distinction can be drawn between prudent self-pacing from experience (voluntary), vs. anticipatory regulation (partially voluntary) and peripheral fatigue (involuntary).

Problems arise with the anticipatory regulation, however, when the anticipated effort turns out not to be true – when the hill is longer than you thought or the amount of time required to maintain the effort is greater. This situation is what separates the theory of anticipatory regulation from voluntary pacing strategy. According to the theory, the mental regulation of effort is partially involuntary and happens at a subconscious level. When confronted with an effort of unknown duration, your body automatically backs off to a sustainable level. While certain physiological barriers remain (maximum safe core temperature, etc.), the primary effect of incorrect distance/time feedback is on your perceived exertion rather than your performance. In other words, you won’t be able to ride or run faster, but your misery level will increase or decline according to the feedback.

Could I have stuck with my ambitious pace had the route not been changed? I don’t know, but I do know that it would have been less miserable!

1 comment:

I liked what you said here, I have experienced this many times. The whole knowing the course before you race thing lets your body know how much to push. I had a great example of this happen when I was piloting a tandem and we were doing a route which we did not know that had some climbs. I was in a more sustained effort mode, while my stoker thought the climb ended, so was pushing hard basically blowup at the blind turn where we went up again.

Post a Comment